Based on: Sarah A. Lanier’s book Foreign to Familiar. McDougal Publishing: 2000

A common mistake that I have seen made in international gatherings is to ask the people present to give an opinion on a certain subject. The American will readily stand up and give his or her opinion, but the Kenyan will not. He will not speak until he has had time to consult his group. If he already knows how the group feels about a certain subject, he can speak, representing not his own opinion, but the consensus of the group he represents. The result is that one Kenyan voice may represent twenty other individuals, while one American voice may represent just that one person.

~ Foreign to Familiar by Sarah A. Lanier (pg 42-43)

Learning Your Identity

Growing up in the United States, children are usually encouraged to think for themselves. They are taught phrases like, “Don’t worry about them, worry about yourself” and “Be yourself, everyone else is already taken.” Most direct cultures*, such as the US, produce adults who have crafted their own opinions and defend them, sometimes without truly listening to the other side. “You do you” is a common phrase used by the younger generations, specifically in America, which loosely means “be yourself” or “do what you want” without worrying about what others think or how it affects them.

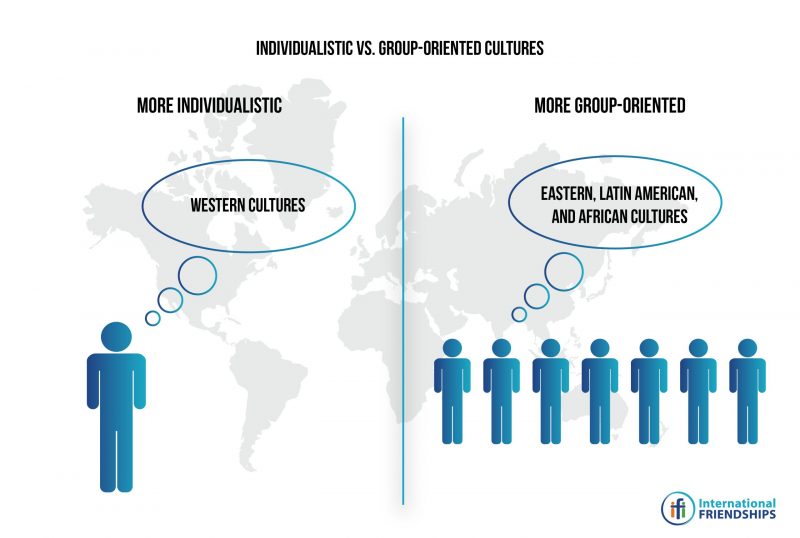

The opposite is true in indirect cultures*. Instead of individuality, children are taught to belong within a specific group such as a family, a tribe, and/or a village. Sarah A. Lanier explores the differences between cultures that are group-oriented vs. those that are individualistic in her book Foreign to Familiar. Group-oriented cultures are mainly indirect cultures and individualistic cultures are mainly direct cultures. (Read more about direct and indirect cultures in: 3 characteristics of an indirect communicator).

Opinions Expressed By the Group vs. For the Group

In a group-oriented culture no one ever stands alone. Everyone takes care of everyone in their group saying, “we are a community and must share our food, private lives, homes, and even opinions, to serve the whole.” This way of thinking begets behavior that is inclusive rather than independent, as it is in direct cultures.

In a group-oriented culture no one ever stands alone. Everyone takes care of everyone in their group saying, “we are a community and must share our food, private lives, homes, and even opinions, to serve the whole.” This way of thinking begets behavior that is inclusive rather than independent, as it is in direct cultures.

Sarah presents an example of how this like-mindedness vs independent thinking can impact the way opinions are expressed among cultures in her book, Foreign to Familiar. At a conference where many languages were represented, the plenary sessions and most of the workshops were conducted in English. There was discussion amongst the leadership (made up of mainly direct culture individuals) about whether or not to have translation from the podium or simultaneous translations for the various languages to save time. Sarah relates what happened, saying:

As various individuals voiced their opinions, it was obvious that simultaneous translation was the preference of the group.

Then a man from Bolivia spoke up and quietly explained the difficulty translators had with simultaneous translation. They were only able to hear half sentences because they did not have time to finish translating a sentence before the speaker was on to the next one. He also explained that alternating translation helped those who spoke English as a second language. The time gap after each sentence allowed the person time to assimilate better what was being said. This is true even if he or she does not understand the translation.

The head of the leadership heard the Bolivian, but then said, “Good point, but the majority seem to think it’s not worth the loss of time on the podium to have the alternating translation. (pg 43-44)

What the head of leadership failed to recognize in this scenario was that the Bolivian man was representing the majority. Others from his same group were not sharing their same thoughts because they had been represented by the Bolivian man and did not believe they needed, as individuals, to be heard. The one vote from the group-oriented culture must have equaled as many as twenty of the individualistic culture, but in comparison to the one Bolivian man who spoke up, the people of the individualistic cultures all spoke up for themselves, making their vote seem to be the majority. Paired with the indirect cultures’ reluctance to state their preferences directly (see 3 characteristics of an Indirect Communicator), the gathering had a very inaccurate representation of the desires of the majority. In cases like these, leaders will need to find ways to give greater weight to inputs from someone representing their whole group in order to make sure the results truly represent the entirety of the gathering.

Shame to the Group vs. Embarrassment to the Individual

Children in a group-oriented culture are taught that their actions, whether good or bad, reflect on the group they belong to as a whole, not just themselves.  They must behave in a way that brings honor to their group’s name, not shame. An example of how people from group-oriented cultures are tied to “belonging” to their families is shown on page 44 of Sarah’s book when she was walking in her neighborhood only to be followed by a couple of Arab boys who were making lewd remarks at her in Arabic:

They must behave in a way that brings honor to their group’s name, not shame. An example of how people from group-oriented cultures are tied to “belonging” to their families is shown on page 44 of Sarah’s book when she was walking in her neighborhood only to be followed by a couple of Arab boys who were making lewd remarks at her in Arabic:

To their surprise, I turned around and confronted them, “What is your family name?” I asked.

Shocked that I understood what they were saying, they asked, “Why do you want to know?”

I said, “I want to know which families you boys belong to so I can tell your fathers how you are behaving in public. When they hear how you are shaming the family by your behavior, they will give you the discipline you need.”

“No! No!” they pleaded. “Don’t tell our parents. We were just joking around and didn’t mean any disrespect. We’re sorry.” And they scampered away.

Knowing they were from an Arab culture (indirect culture), Sarah assumed that their group identity was probably strong. This meant that their individual actions would reflect on their family because the individual does not stand alone, and is never the only one affected by his own actions. The mention of their families made the boys realize that they could not get by with their bad behavior without it affecting their entire families as well. If this same circumstance were to have happened with two American teenagers instead, it is likely that the mention of their families would have little to no effect on them as they do not consider their own actions as representing their family, but merely as a reflection of themselves.

Working on a Culturally Diverse Team

Although working on a team with varied cultural backgrounds can be a huge asset, it also comes with its own struggles, as there often are large differences in the way team hierarchy and leadership are viewed. An individualistic culture typically views being a team member as being an equal to the other members on the team. Granted, the team’s leader has more responsibility and directing power, but they most likely do not expect to make all the decisions for the group. Particularly among Western, individualistic cultures, team members often speak up and take initiative, voicing their own opinions and ideas based on their personal insights.

In group-oriented cultures, to take initiative would be seen as rude to the team leader who is seen as “stronger” and more directive. Team members in a group-oriented culture will wait to be called upon before asserting themselves or their ideas. This can be referred to as the “tallest poppy syndrome,” in which, if one member of the group takes the initiative to assert himself or herself, the group will pull him back to see that he fits into the group. In group-oriented cultures, it is expected that the leader will lead and the team members will cooperate out of respect for the authority of the leader. (This can vary with the type of team involved or within the individual customs of a country.)

In group-oriented cultures, to take initiative would be seen as rude to the team leader who is seen as “stronger” and more directive. Team members in a group-oriented culture will wait to be called upon before asserting themselves or their ideas. This can be referred to as the “tallest poppy syndrome,” in which, if one member of the group takes the initiative to assert himself or herself, the group will pull him back to see that he fits into the group. In group-oriented cultures, it is expected that the leader will lead and the team members will cooperate out of respect for the authority of the leader. (This can vary with the type of team involved or within the individual customs of a country.)

When individualistic and group-oriented people work together, these differences in beliefs can cause lots of misunderstandings. People from individualistic backgrounds will expect initiative and ideas from those of a group background, while those from a group background will only give what they believe is required of them in the role that they are in, not wanting to step on the toes of the leader. Likewise, when an individual takes initiative within a group-oriented culture in a team context when it is not their role to do so, they would be seen as being inappropriate and may be ignored or rebuked. Sarah shares an example of working cross culturally and how those misunderstandings could arise:

A team of young people from individualistic cultures went to Africa for three months of service. The team leader was African. Some of the team members later complained that they were not included in the decisions of the day, nor communicated with personally on what was happening. They were just “told what to do.” As I talked with the leader later, he was surprised to hear that they felt a need for communication. From his perspective, he had told them what they needed to know when they needed to know it.

For an individualistic culture to think in terms of “we” instead of “I” can be a major switch from what they are used to. Similarly, for someone who is used to the group culture of belonging, to be thrust into a culture of individualism can be increasingly lonely. It would be a challenge to make decisions based on themselves (which would seem rude) instead of what the group as a whole wants. Although difficult, it is helpful to understand the context one is entering, especially when working on a team that includes people from different cultural backgrounds.

In Conclusion

Although differences between the individualistic cultures and group-oriented cultures can cause significant misunderstandings, this does not need to be the case. When traveling to a culture different from your own (or hosting an individual from a different culture) be sure to do your research on what values they hold. Then, with respect for their culture as well as your own, be sure to communicate expectations and any misunderstandings that may arise to find the best way to move forward and continue a growing relationship!

*For more on direct and indirect communication, read our article on 3 Characteristics of an Indirect Communicator